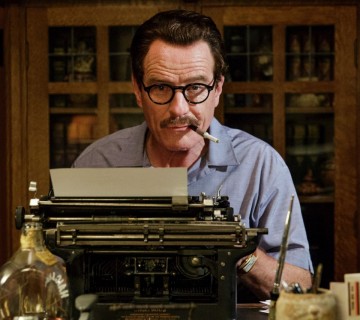

This is the winning entry from our March contest (thanks for all the great submissions, everyone!) and it serves as the introduction to a series of articles – an online screenwriting workshop, if you will – by Heidi Fuhr, wherein she will break down the ten specific plot points that, whether you’ll admit it or not, make up almost every great story you’ve ever heard or seen. And to put it all into a familiar context, she will be using the pilot episode of AMC’s Breaking Bad as an example.

Buckle up and take note. Here we go.

INTRODUCTION: How Do You Plot Character-Driven Stories?

Is your screenplay-in-progress stuck? Do you have nearly completed screenplays wasting away on your hard drive because you know they’re just not quite . . . right? Are you waiting for the elusive muse of creative genius to strike? Do you have an amazing character, but you can’t figure out what should happen to him? Or do you have an exciting plot, but the protagonist could be anybody?

The best screenplays strike a fine balance between plot and character. Like space and time, plot and character are inextricably linked. I know – it sounds like alchemy, but it isn’t. Creating a good screenplay isn’t as intangible as we like to think. In fact, it’s almost formulaic. Yes, I know; the word “formula” has a sleazy ring to it. We’re artists, not mathematicians! I don’t mean to suggest that screenplays can be slapped together by just anyone who can follow a recipe (unless you write for network TV, maybe). Of course it’s not that easy. But neither is it magical, nor bestowed upon us by story Gods, for whom we’re merely scribes. It’s a skill that can be broken into parts and mastered, with practice.

Almost every great story strikes ten specific plot points in a given order. Yes, these plot points can also be seen in stupid, predictable summer blockbusters; that’s why they make so much money, because they scratch an itch for story that lies deep in the human soul. But the very same plot points can also be found in the most sophisticated independent films, the most prestigious award-winners, and the most revered literary fiction from Homer to David Foster Wallace.

As humans, artists, and critical examiners of fiction in all its forms, the story formula is already installed on our creative hard drives. But story is so intuitive, it can be difficult to recognize how it works. As you learn the basics, you’ll begin to recognize how it manifests in the films and television you watch.

At first, it will seem simplistic. It’s easy to recognize the formula in cheesy, crowd-pleasing slapstick comedy films of the Adam Sandler/Jack Black ilk or the action-packed blockbusters that value explosions and sex scenes over artistic substance. But the more you look for it in the films and television you enjoy, the more you’ll see how versatile it is. In the right hands, this formula can be used with subtlety and sophistication to create an infinite variety of fresh, surprising, and deeply complex stories. This blog series will explain each point of the plot formula, but it will also look closely at how character is interwoven from beginning to end.

The plot structure has been used in some form by generations of screenwriters, centuries of novelists, and eons of storytellers. From Aristotle’s Poetics to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey to Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet, writers and scholars have already done the work of nailing down the science of telling a great story. As a screenwriter, you can save a lot of time, and take the mystery out of solving story problems, by learning the age-old formula of storytelling.

PART I – and the rest of the series can be found here, as the articles are published.

Image courtesy Neighborhood Nini

Join the Conversation →