In the last article of our screenwriting series, we talked about stasis, the before situation of the protagonist. Here, we’ll cover the inciting incident. In the next article, we’ll finish out act one with the third plot point, the call to action. You can follow the series ‘How Do You Plot Character-Driven Stories?’ by Heidi Fuhr here.

ACT ONE – PLOT POINT II: THE INCITING INCIDENT

At this point in the story, something happens that interrupts the stability of the protagonist’s before situation, or stasis. Usually, the inciting incident is just that – an incident. Unlike most examples of stasis, it happens quickly. This incident doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing. In a basic love story, for example, this is usually when the protagonist first meets the love interest. The important thing about the inciting incident is that it causes the necessity for change. In the basic love story, change becomes necessary because the protagonist suddenly realizes he needs to be with the object of his affection, or he realizes he can’t bear the loneliness anymore.

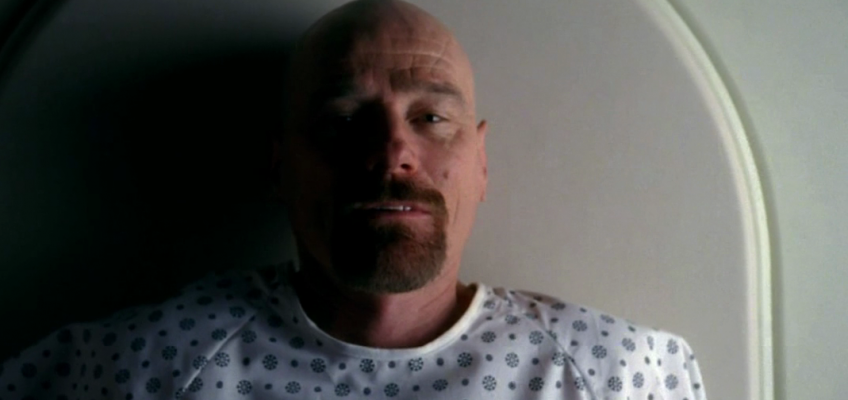

Inciting Incident in Breaking Bad

In Breaking Bad, Walt collapses at the car wash and is taken to the emergency room in an ambulance he can’t afford. There, he’s told he has end-stage lung cancer.

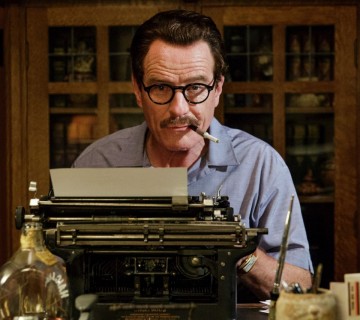

In most stories where the inciting incident is the protagonist finding out about his imminent death, the concrete objective (or external conflict) that follows is to figure out a way to stay alive. This isn’t the case here. Walt is a scientist. He knows he can’t save himself. No, Walt’s concrete objective is to plan for his family’s financial security after he’s gone. In simpler terms, the external objective is to get money, and the internal objective – which is closely aligned with the character debits in Walt’s stasis set-up – is to finally be a man. Providing for his family’s future is Walt’s last chance to seize control of his situation, to be a doer, to be potent, and to get respect. But how does a guy like Walt – who makes so little teaching high school that he has to work a second job at a car wash just to make ends meet, whose disabled son will soon be going to college, whose unemployed pregnant wife and unborn baby will incur huge hospital bills in the near future, whose own time is running out – manage to do that? We’ll find out in the upcoming article, the call to action. But first, a few more notes on inciting incidents.

Other examples of inciting incident

School of Rock: Jack Black’s character is facing eviction because his roommate’s girlfriend has had enough of his inability to pay the rent.

Amadeus: Austrian court composer Salieri can no longer ignore his musical mediocrity when Mozart comes to town.

The Big Lebowski: The Dude is going about his business when two men break into his house and demand money, mistaking him for another Lebowski. In the parlance of The Dude’s world, the Chinaman pisses on his rug. The Dude’s stasis situation is so simple (in fact, it passes almost without notice), the ruined rug is the impetus for change, because that rug really tied the room together.

Side notes: Story arcs and ticking time bombs

There are several ways to deal with story arc in TV. Some shows only use one type, some use a combination. Breaking Bad has three types of story arc. The first is the series story arc, which plays out from the beginning of the first season to the end of the last. The second is the seasonal story arc, where each season has its own set of plot points, its own major antagonists and conflicts. The third is the episodic story arc, which lasts only one episode. The act one stuff I’m covering here applies to all three: the stasis, inciting incident, and call to action of the pilot episode also serve as act one for season one and for the whole series.

Walt’s inciting incident also functions as a ticking time bomb, a plot device that essentially works just like it sounds – sometimes it’s even a literal ticking time bomb. Any time a ticking time bomb is introduced, it must either be defused or explode (figuratively, if not literally). In Walt’s case, because of the dramatic way the cancer was introduced and its integral role in the action of the story, it has to play out. Walt either has to die from it, or the cancer has to be cured in an equally dramatic way. If it didn’t – if, for example, it went quietly into remission and ceased to be a driving force of the action – the story wouldn’t be satisfying. That said, it’s okay for this ticking time bomb to stay active at the end of the episodic plot arc, and even the seasonal story arc, but it has to be addressed by the end of the series story arc.

Join the Conversation →