This is the second article in our on-going series about the entire filmmaking process, from idea through pre-production, shooting and post-production all the way to distribution. We’re following the production of the ultra low-budget feature film, The Storyteller, in real time (more or less), which gives us a unique opportunity to give you an open and honest look at what it’s actually like to make a movie. Read the introduction to the series here – or get right to it…

Last time we discussed ideas – where they come from and which ones to pursue. Once the light bulb has come on and the idea has formed, the journey to the first draft begins. Books, articles, websites, even entire classes are devoted to understanding and giving writers tools to navigate this daunting and, at times, hair pulling journey. Every writer’s method is unique to his or her writing process. In addition, a writer’s process is always in a state of development. One story might suggest a more outlined approach, while another might be hindered by it. This process is even more unique when two writers collaborate.

For the majority of the writing process, Joe and I would have a long conversation about the world, the characters, and the scenes, and then I would take all of this and begin writing. Usually I would stop after 15 or 20 pages and send to Joe to make sure it was moving in the right direction. Joe would read over the pages, make detailed notes, he and I would discuss them at length, and then I would implement them, and write forward on the next 15-20 pages. After we had a “complete” first draft, and could see more clearly where the story was headed, then Joe and I began trading drafts. He would take the most current draft and go through it, making changes and adjustments, he would send to me, I would do a pass through it, and we traded back and forth until we both felt satisfied with the flow. – Rachel Noll, co-writer and producer of The Storyteller

To write beat sheet or not? That is the question.

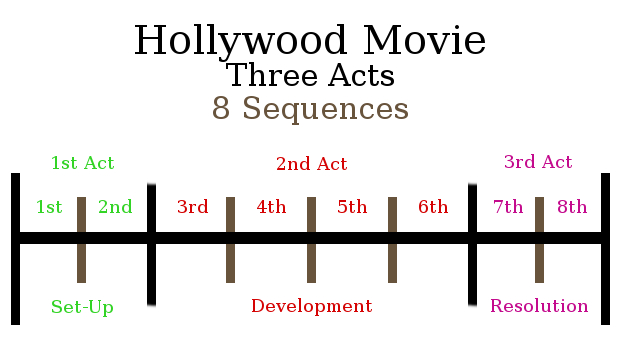

A typical fictional story has THREE ACTS, simply the beginning, middle and end. The beat sheet – a method famously explored in Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat – is at its core, a breakdown of your main characters progression through those three acts. There are a total of 8 beats (or sequences) in any give story. In a nutshell:

Each sequence is a portion of the story that leads the character to the next. Writing down your characters predicament in each sequence and whether they succeed or fail allows you to outline the entire story.

And check out this helpful video to learn more about 8 sequences:

It’s important to get ideas down on paper, but a lot of it has to happen in your head first. Most of my ideas come at strange times during the day – while I’m out in the woods walking or in the shower or when I wake up in the morning lying in bed. It’s a form of meditation for me – I never was too good at meditating and stopping the “monkey mind” by emptying it – I’d prefer to calm it by tapping into a story or a character or a concept. – Joe Crump, co-writer and director of The Storyteller

For some writers, a beat sheet is the most outlining they will do. Others prefer to expand that outline and break each sequence down into the individual scenes that will make up each sequence. This is most famously done on index cards, one card equaling one scene. And some writers prefer to take their idea and find the structure during their journey of writing the first draft. A writer’s process doesn’t mean getting from point A to point B will be easy – it means you’ll get there.

Even if you don’t write a beat sheet or outline, breaking down other movies, similar in tone or character arc to yours, is a great way to sharpen your storytelling skills. Wondering where to start? Check out this article by yours truly that broke down The Graduate.

Let’s Be Clear: Your writing process is YOUR writing process! Understanding a three-act structure and/or diving into an 8-sequence structure does NOT make your story formulaic. Think of it like this: every person on this planet is unique, but we are all made up of bones that connect to make our skeleton. So too is a three act structure your story’s skeleton.

Communication is key is ANY kind of collaboration. This is especially true in writing because a story can’t be developed when its writers (no pun intended) aren’t on the same page. But when two writers come together, they can bring out the best in each other and create something special.

Talk about a collaboration! Remember this great scene?

For me, the benefit is having someone to bounce ideas off of. You can get stuck in your own head sometimes and circle around a problem scene or moment. With two people, there is always an alternative perspective to be shared. We help un-stick and inspire each other. Collaborating can be tricky though. I have had a really hard time collaborating in the past… Joe and I have found a very natural rhythm, and we are very much on the same page about the stories we are working on, and the way we delegate the work. In my experience, this kind of an easy partnership is a rare thing. Its like finding a romantic partner, or a dance partner…. you have to be in sync with each other, and if you aren’t, it can be more detrimental than helpful. – Rachel Noll, co-writer and producer of The Storyteller

First draft = vomit draft.

Whether you have outlined every detail of your story or took to the page having no idea where the story would end, the first draft is ALWAYS about getting the story out, hence the term vomit draft. The first draft is not about making the script pretty or even having every moment make perfect sense. It’s about getting the idea written.

Rewriting is probably the most important part of the process for me. We will work on a script until we think it’s the best it can be. Then we send it out to friends and to a few paid script readers, who don’t know us, for feedback. They come back with comments – some of them aren’t helpful, but when you start to look at multiple comments from several people, you can sometimes see a pattern and discover things they never articulated, but are buried beneath the surface. When that happens, we do another draft – and then we follow this same process again and again until we shoot. It’s never really done. There is always another layer, another nuance that can be added. - Joe Crump, co-writer and director of The Storyteller

Typing the words ”the end” is a victory, one that not every writer gets to. And it’s after that victory that the refining process begins. This doesn’t mean adding pages or coming up with a twist ending. It means going back and analyzing “what works in this draft? What doesn’t work? What is this story really about?” Again, you can plan and plan and plan, but once you have that story written, only then can you really take a step back and see the difference between the story you envisioned and the story you wrote. It’s then that the process morphs into taking the story where it wants to go!

Join us next time when we’ll discuss copyrighting – how and why do you copyright your script? Until then here’s a fun clip that shows the benefits of collaboration:

Join the Conversation →