Moving on from our previous post, which covered the Inciting Incident, today’s post will be addressing the third plot point you need to be familiar with; the Call To Action. As always, Heidi Fuhr, is guiding us through the mechanics of engaging script writing, using the pilot episode of Breaking Bad as an example. Follow the series here and be sure to read the introduction.

This article will cover the third and final plot point of act one. To quickly review, act one consists of three plot points: stasis, the inciting incident, and the call to action.

In the last article we looked at how the inciting incident causes the instability in the protagonist’s world. Now, he has to do something to restore that stability – to return to some form of stasis. The call to action is the “invitation” to the journey that will directly resolve the external conflict. Though the protagonist doesn’t know it yet, the journey will also address the internal conflict. The more internal conflict there is, the more character-driven the story is.

In the classical sense, the call to action is a literal invitation, often from a mentor or spiritual guide, like Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings. Many protagonists in old-school “hero’s journeys” follow that model, where the hero is “chosen” for the quest because an authority figure or mystical guide recognizes some singular specialness within them. Contemporary realistic stories tend to translate the call to action less literally. The impetus for the journey can come from within, or the idea can be implanted in the hero by more abstract means, like a dream or an observation. In other words, in modern stories, the protagonist is more likely to have agency in choosing how to solve the problem. In either case, there is often, but not always, a moment of indecision before the protagonist accepts the “quest” (again, don’t think about these terms too literally).

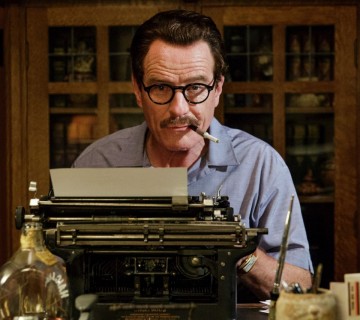

Call to Action in Breaking Bad

Walter White has just learned of his imminent death. He doesn’t tell his family yet; first he needs a plan to secure their financial future. If he does one thing right in his whole life, it’ll be this. That evening, he sits in his back yard and flicks lit matches into the pool, an action he repeats every season when heavy decision-making is called for. It’s obvious he’s looking for a solution to his inciting incident. Having seen news footage of the huge pile of cash seized at a recent drug bust, Walt calls his DEA-agent brother-in-law Hank and asks if he can ride along next time he raids a meth lab.

There’s also a second call to action in this episode, but strangely, it doesn’t happen to Walt: When Walt is on the ride-along, he sees his old student-turned-drug-dealer, Jesse Pinkman, fleeing the scene. Later, he goes to Jesse’s house and proposes teaming up with him to make and sell meth. Jesse doesn’t want to get involved until Walt pressures him by threatening to turn him in to the DEA.

It’s arguable that this moment functions as a call to action. After all, Jesse isn’t the protagonist. However, if you’ve watched at least a season of the show, you might have noticed that Jesse actually becomes the moral center of the story at times. Even though he’s an addict and a career criminal, he’s less prone to being blinded by ego than Walt is. Eventually, Walt and Jesse become two sides of the protagonist coin.

Other Examples of Calls to Action

- The Big Lebowski: The Dude is actually one of the few characters I can think of that have almost no agency at all (but this is utterly appropriate for his character). His call to action happens when the other Lebowski asks him to deliver the ransom money to his wife Bunny’s kidnappers.

- Game of Thrones (pilot episode): Ned Stark is asked to go to King’s Landing to serve as the Hand of the King for Robert Baratheon.

Tag along as we soon venture into Act II and the plot points that will carry the story onward.

Join the Conversation →